A Critical Look at MATLAB Array Types

Introduction

Matlab is a numerical computing platform and programming language with a strong focus on multi-dimensional arrays and linear algebra. In this post I examine the array types in matlab and discuss their design.

Matlab’s Array Types

Matlab has two primary array types, the matrix and the cell array. The matrix is a dynamic array of contiguous memory, which can contain a number of different element types and has convenient syntax for multi-dimensional indexing and linear algebra operations. The cell array is ostensibly a dynamic array of pointers to objects, and can be used for storing elements that can’t be stored contiguously, such as matrices, other cell arrays, and non-homogenous types. These two types roughly correspond to ‘unboxed’ and ‘boxed’ arrays in other languages.

Basic Operations

You can create a matrix like this,

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

and index into it like this.

numbers(3)

ans =

3

Cell arrays are created with curly braces,

items = {1, 'hello', 3, [4, 5, 6], []};

and indexed with curly braces as well.

items{4}

ans =

4 5 6

Having a different syntax for the same action performed with two different types is an odd choice. Generally, high level programming languages seek to abstract over implementation details. Indexing into a collection type should work the same regardless of that types internal machinery, allowing functions that work with collections of data to target a unified interface and automatically work with a variety of types. Deliberately having different indexing syntax complicates this kind of intuitive polymorphism. Additionally, the lack of defined interfaces for basic operations makes creating user defined types that work well within the existing ecosystem more challenging. As we continue, lets see if we can uncover the rationale behind this design.

For Loops

For loops are the predominant (non vectorized) way to iterate over the elements of a collection in matlab. Writing ‘for element = array’ binds element to each item in the collection ‘array’ in the loop scope. This is the equivalent of the more intuitive (here the equal sign does something completely different than it does everywhere else in matlab) ‘for element in array’ in other languages.

Looping Over Matrices

Here’s and example that displays each element in a matrix.

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

for element = numbers

disp(element);

end

1

2

3

4

5

Looping Over Cell Arrays

Observe what happens when we iterate over a cell array.

items = {1, 'hello', 3, [4, 5, 6], []};

for element = items

disp(element)

end

{[1]}

{'hello'}

{[3]}

{[4 5 6]}

{0×0 double}

Instead of ‘element’ being bound to each element in the collection as it is for matrices, ‘element’ is bound to a cell array containing a single element of ‘items’ at each iteration. If you want to replicate the behavior of the first loop for a cell array, you need to index ‘element’ with {} like so.

items = {1, 'hello', 3, [4, 5, 6], []};

for element = items

disp(element{1})

end

1

hello

3

4 5 6

Unfortunately this makes writing code that can operate on both cell arrays and matrices more complicated.

So What’s Going On?

To understand why for loops work like this, we need to understand a couple implementation details about matlab. The first thing to grasp is that all values are matrices. A single object is a matrix with size 1 by 1. Indexing a single element of a matrix with () actually returns another matrix with a single element. This is the design that matlab chose in order to facilitate indexing sub matrices.

Creating a 3 by 3 matrix.

a = [1, 2, 3 ; 4, 5, 6 ; 7, 8, 9]

a =

1 2 3

4 5 6

7 8 9

Extracting a 2 by 2 sub matrix by indexing with the range [1, 2] on both axes.

a(1:2, 1:2)

ans =

1 2

4 5

In matlab, indexing a collection with () always returns a collection of the same type. In fact, you can index cell arrays with () as well, it returns a cell array containing the elements at the requested indices.

items = {1, 'hello', 3, [4, 5, 6], []};

items(2:4)

ans =

1×3 cell array

{'hello'} {[3]} {[4 5 6]}

This is the case even if you request just one element.

items(3)

ans =

1×1 cell array

{[3]}

For loops in matlab index collections using (), explaining our strange looking result when the collection is a cell array. When you index a cell array with {}, matlab dereferences the pointers and returns the objects themselves, rather than another cell array.

Comma Separated Lists

What happens if we try to dereference multiple elements from a cell array with {}? Lets try it.

items = {1, 'hello', 3, [4, 5, 6], []};

items{2:4}

ans =

'hello'

ans =

3

ans =

4 5 6

This time matlab returned three distinct things, but its not immediately clear exactly what type {} is returning. If we try to store the returned value in a variable, we only get one thing.

b = items{2:4}

b =

'hello'

Indexing multiple items with {} returns one of matlabs lesser known (and most confusing) types, the comma separated list. This data type cannot be stored in a variable, but can be directly inserted into an expression anywhere that would normally accept items separated by commas. For instance, comma separated lists can be used to create matrices,

elements = {1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 12};

mat = [elements{2:4}]

mat =

3 5 6

if cell elements are different types strange conversions may occur!

or, perhaps more usefully, pass arguments to functions. Here we are adding up values by inputting a matrix and the string ‘all’ to specify which elements should be summed.

arguments = {[1, 2 ; 3, 4 ; 5, 6], 'all'}

sum(arguments{:})

arguments =

1×2 cell array

{3×2 double} {'all'}

ans =

21

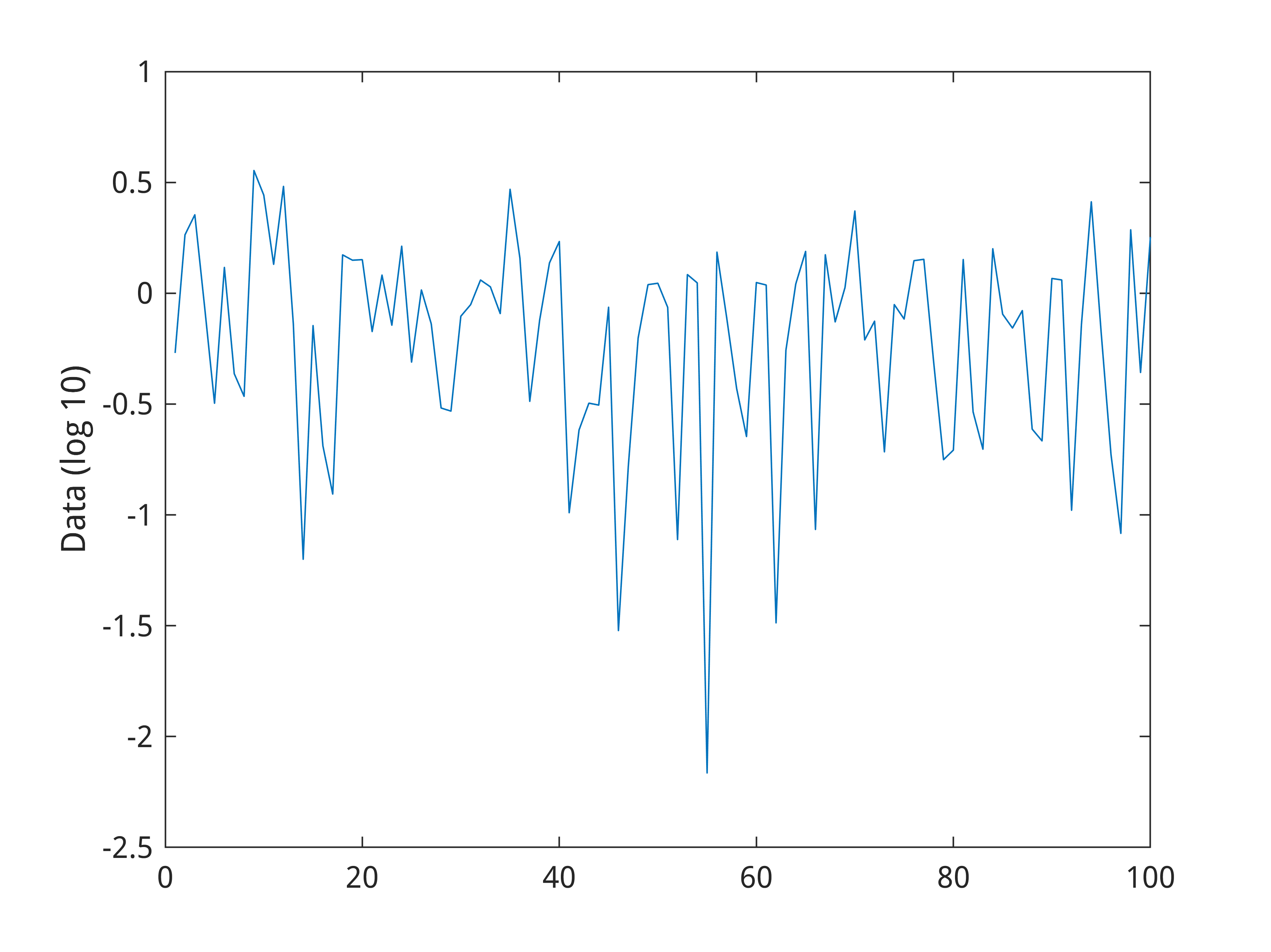

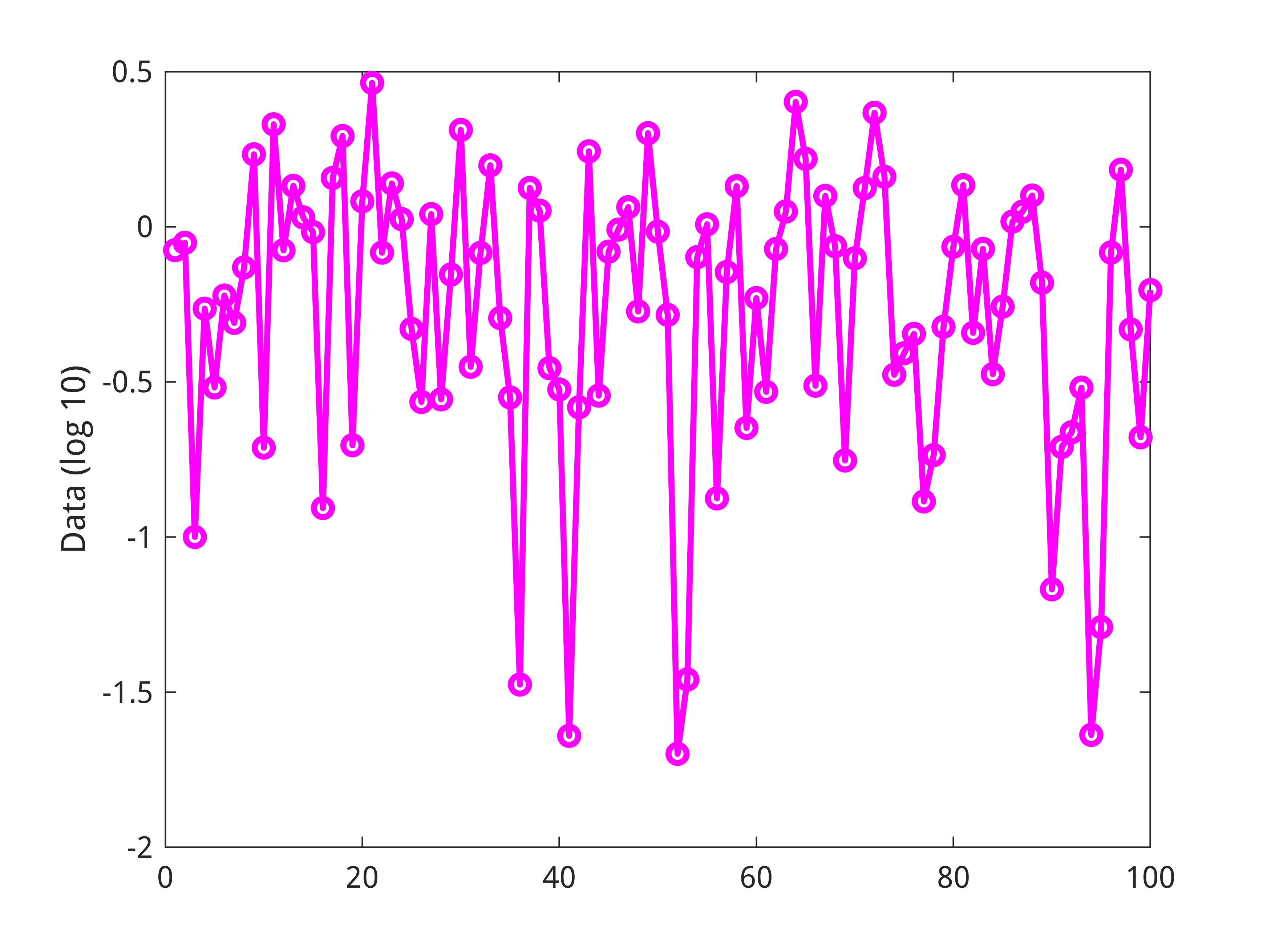

Variadic functions in matlab make use of these mechanics. The special identifiers ‘varargin’ and ‘varargout’ capture the input and output to a function as cell arrays, making passing arguments up and down the call stack a breeze. For example, here is a function that produces a customized figure, but allows the caller to pass arguments to dictate the line style.

function fig = myCustomLogPlot(data, varargin)

logData = log10(abs(data));

fig = figure();

plot(logData, varargin{:});

ylabel('Data (log 10)');

end

myCustomLogPlot(randn(100,1));

myCustomLogPlot(randn(100,1), 'mo-', 'LineWidth', 2);

This examples uses the older, simpler syntax. In 2019b a new keyword block ‘arguments’ was added that lets you do even more with variable arguments.

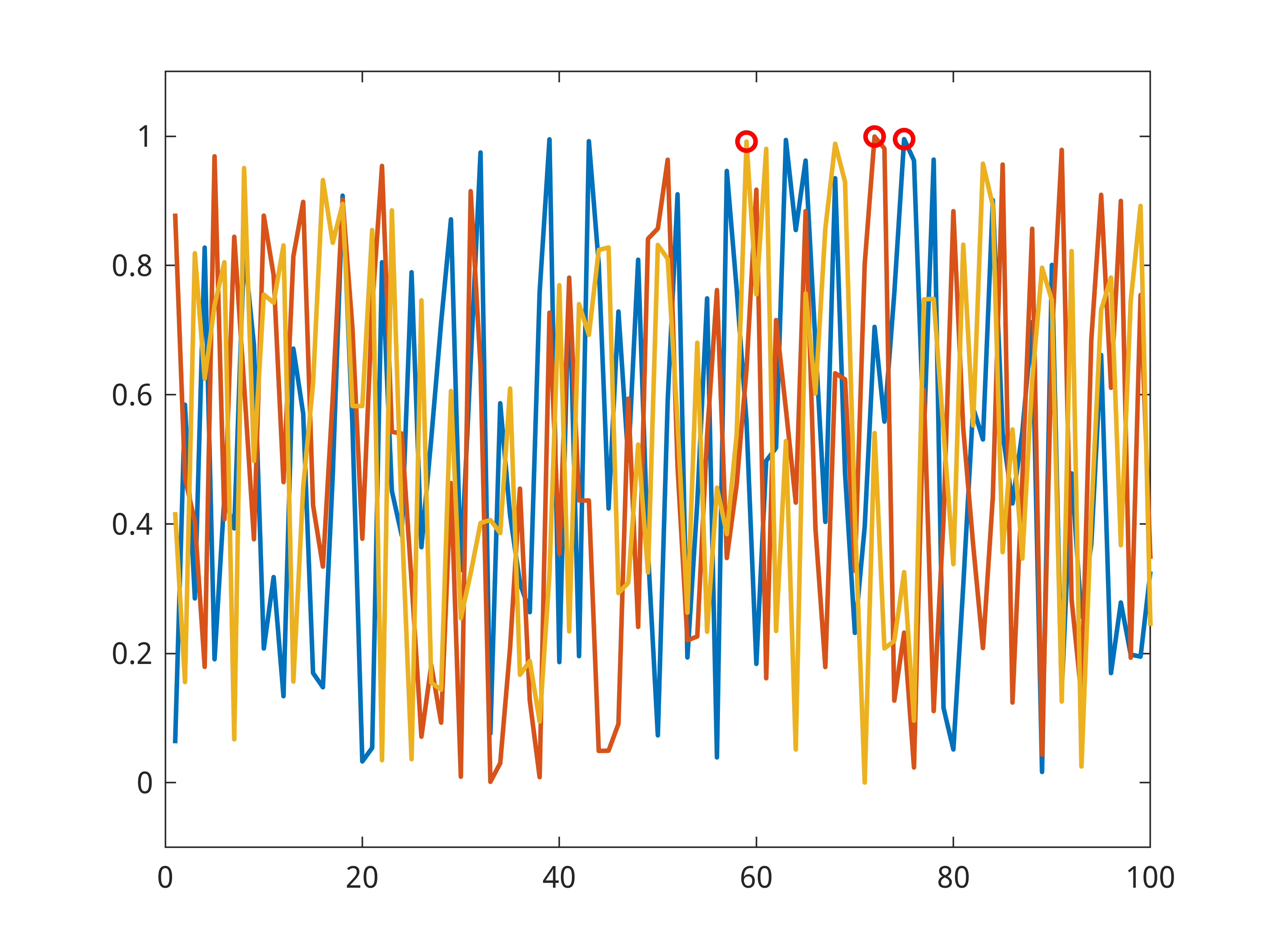

Comma separated lists can also be used to capture multiple return values from a function, in this case the index and value of the maximum points in some random data. We can index the ‘points’ cell array backwards to input the arguments in the correct order.

data = rand(100, 3);

[points{1:2}] = max(data);

figure();

plot(data, 'LineWidth', 1.5); hold on;

plot(points{end:-1:1}, 'ro', 'LineWidth', 1.5);

ylim([-0.1, 1.1]);

There are a lot of tricks with comma separated lists, and various useful things you can do by converting between the three collection types. I may expand on this topic at a future time.

Conclusion

Matlab is internally consistent in the way it indexes matrices and cell arrays. Mechanically, () does the same thing to both data types, but there is one critical difference. In matlab, a single element matrix behaves like a value, while a single element cell array does not.

Arithmetic can be done directly on single element matrices,

a = [10]; % a single value in a matrix

a + 2

ans =

12

but not on a single element cell array.

b = {10}; % a single value in a cell array

b + 2

Operator '+' is not supported for operands of type 'cell'.

This difference means that in practice, using the two collection types can be counter intuitive. The problem here really boils down to the abstraction boundaries being drawn in the wrong place. The two types duplicate 90% of the functionality between them, but the remaining 10% difference is enough that you usually have to write separate code to do the same thing with each. (Examples include the built in functions arrayfun and cellfun) If matlab had a dedicated reference/pointer type, there wouldn’t really be a need for a second kind of array, since you could just create a regular matrix with references as its elements. In fact, I often want to index matrices with {} to spit out the elements in a comma separated list, but currently I have to convert the matrix to a cell array first. Really there is no intrinsic link between an array of object references and being able to split the elements into a comma separated list, its just a coincidental quirk of matlab’s design. Refactoring those two properties to be independent would make matlab code both more consistent and more flexible.

Part of the problem is that matlab has no real way to define abstract behaviors independent of the specific implementations and syntax. If () and {} corresponded to abstract interfaces with defined type signatures, it would be more obvious how they work and clearer which behaviors should be independent.

I should note that matlab has a fully featured OOP framework with abstract classes, but this is not well integrated with the basic functionality. The user can apply this framework to define their own systems of behaviors, but you’re still stuck with the specific implementations of the built in types, which are not expressed anywhere in user accessible code. Additionally the lack of type signatures for methods in matlab limits how specific you can be with abstract classes.

These problems are emblematic of a general trend of inconsistency in design that often restricts composability. The matlab programming language has no real way of talking about itself, no way within the language to instruct the programmer on its operation or enable them to easily make extensions that work consistently with the existing system. The oddities in its design can make grasping the important concepts difficult and the knowledge gained is rarely applicable to other programming languages.

Practically, its probably best to prefer using matrices to cell arrays wherever possible, and avoid using for loops altogether. Matlab really shines when writing vectorized code that operates on the level of vectors and matrices, rather than dealing with individual elements. This is both better for performance and much more ergonomic for the programmer, but unfortunately often leads to code that is less obvious in intent and more difficult to read.